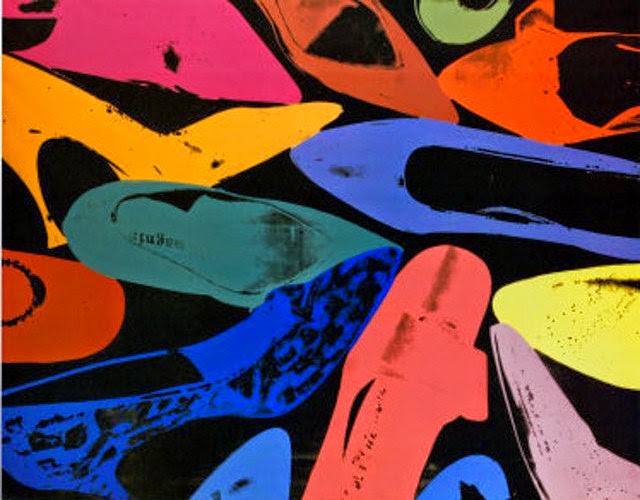

Why do so many relationships end up in breakups, separation, and/or divorce? Why is it that in many situations when we love our partner, they don't love us; and when they love us, we don't love them? Why is it that every relationship promises to be different, but it ends up being very similar to the old relationships? Why do we repeat our patterns – like a broken record? Neurochemistry of Love - Testosterone and Estrogen are the primary sex hormones. Adrenalin is a hormone that is released in the body of a person who is feeling a strong emotion (such as excitement, fear, or anger) and that causes the heart to beat faster and gives the person more energy. Dopamine – The dopamine system is strongly associated with the reward system of the brain. Dopamine is released in areas such as the nucleus accumbens and prefrontal cortex as a result of experiencing natural rewards such as food, sex, and neutral stimuli that become associated with them. Serotonin is one of love's most important chemicals that may explain why when you’re falling in love, your new lover keeps popping into your thoughts. Oxytocin (The cuddle hormone) is a neurotransmitter in mammals. Oxytocin is normally produced in the hypothalamus and stored in the posterior pituitary gland. It is the hormone of Love! Vasopressin is another important hormone in the long-term commitment stage and is released after sex. Oxytocin and Vasopressin are attachment and bonding hormones. Neuroscience of Love - When a person falls in love, at least 12 areas of the brain work in tandem to release euphoria-inducing chemicals such as dopamine, oxytocin, adrenaline and vasopression. The love feeling also affects sophisticated cognitive functions, such as mental representation, metaphors and body image. Other researchers also found blood levels of nerve growth factor, or NGF, also increased. Those levels were significantly higher in couples who had just fallen in love. This molecule involved plays an important role in the social chemistry of humans. You can just be a loving person for your brain/body to function this way, albeit to a lesser extent! Prerequisites for healthy development of an infant – D.W. Winnicott wirtes: “The mother gazes at the baby in her arms, and the baby gazes at his mother’s face and finds himself therein . . . provided that the mother is really looking at the unique, small, helpless being and not projecting her own expectations, fears and plans for the child. [Otherwise] In that case, the child would find not himself in his mother’s face, but rather the mother’s own projections. This child would remain without a mirror, and for the rest of his life would be seeking this mirror in vain.” Winnicott in this quote tells us why we seek partners who seem to “approve” us and make us feel “good”, “desirable”, and “wanted”, but we are never satisfied and/or our seeking ends in failure. Psychology of Love - A Child (Infant) must experience predictable presence of primary care taker to feel safe and protected. Child (Infant) must experience unconditional love, acceptance, empathy, and nonjudgmental presence of primary care taker to feel that he is worthy of love, he is worth it, he is good, and he is OK. He then believes there is benevolence (goodness) in the world, and people are generally good. The infant splits the object toward whom both love and hate were directed, in two. The good object (idealized) representation is important and is necessary to go on in life. The bad (frustrating, repressing) object is further split into two, namely the repressive object, and the exciting object. Ego identifies with the repressive object (anti-libidinal self), and keeps the original object seeking drive in check. Ego also identifies with the exciting object (libidinal self) and seeks exciting objects in the world. It is the idealized object that many seek initially in their relationships (infatuation stage), which is soon replaced by power struggle (acting out of anti-libidinal self). Some are lucky enough to transcend the power struggle stage and enter the “co-creativity” stage. Fear of Intimacy - Love is not only hard to find, but strange as it may seem, it can be even more difficult to accept and tolerate. Most of us say that we want to find a loving partner, but many of us have deep-seated fears of intimacy that make it difficult to be in a close relationship. Fear of intimacy begins to develop early in life. As children, when we experience rejection and/or emotional pain, we often shut down. We learn not to rely on others as a coping mechanism. After being hurt in our earliest relationships, we fear being hurt again. We are reluctant to take another chance on being loved. If we felt unseen or misunderstood as children, we may have a hard time believing that someone could really love and value us. Or if we do believe they love us, we find all kinds of reasons why they are not the “right” person for us. It is painful to love someone when they don't love us. This is more familiar to us, but painful nonetheless. This is about re-experiencing the pain of deprivation from early contact and holding. It is much more painful to be loved – to open ourselves to love, be vulnerable, and let go of our defenses. This is about re-experiencing the pain of heartbreak (if we risk going there). Our defense mechanism may respond with rejection (rejecting the loving object). This is also much harder to perceive and imagine. There may be a tendency of wanting to pull back and go away, to feel weird in your body, to feel shame, to contact in our chest, etc. A Neuroscience Perspective - Brain is shaped by experience. A new experience results in formation of many neural connections that result in adaptation and response to the experience. Thus our brain is formed (wired) by our experiences starting from our early formative years. Every time a given experience is repeated the corresponding neural networks are strengthened. This statement is a direct corollary of Hebbian axiom which says that the neurons that fire together wire together. Brain can be thought of as an information processing organ (an organ of compare and contrast), in the sense that when faced with a stimulus, it performs very fast correlation-like operations with what it has stored in memory to find the closest match to the stimulus just encountered. The correlations are performed with stored events that are more emotionally significant. Emotional significance is marked by Amygdala – an almond-shape set of neurons located deep in the brain's medial temporal lobe (one in each hemisphere), very close to Hippocampus which manages organizing, storing and retrieving memories. In humans and other mammals, this subcortical brain structure is linked to both fear responses and pleasure. Amygdalae therefore assign emotional significance and information to stimuli. Once the closest match is determined the emotional response will essentially be the same as the response corresponding to the past experience (existing wiring in the brain) with some modifications. This is how we repeat our past. Freud called this phenomenon “Repetition Compulsion”, or the compulsion to repeat past trauma. An implication of the above assertions is that we unconsciously seek to repeat what is known to the brain. Thus we unconsciously seek similar relationships to the ones we have experienced before. And what is even more astonishing is that even if the relationship is inherently different, our behavior will resemble the past relationships (activation of the same neural pathways), thus changing the new relationship, in essence, to be similar the ones we have experienced in the past. After all, that is all that our brain knows! In psychological terms this is known as projective identification. It means that we may project the image of a past relationship onto our current relationship and the partner may identify with the image and act it out – resulting in repetition of the past! This happens since brain will try to compare the current relationship to what it has stored in its neural connections, and respond in the same way. Projection identification then is brain's attempt to adapt to a new experience based on what is learned in the past. This is the reason why our relationships turn out to be very similar to the old ones, as much we try not to repeat our pat “mistakes”! Donald Kalsched (Trauma and the Soul) writes: The act of loving is a terrible risk for everyone, and especially for people who have grown up in emotionally impoverished environments. To really love someone (without symbiotically attaching to them through identification), is to risk losing them, precisely because we live in an insecure, unpredictable world in which death, separation, or abandonment is an ever present reality. Erich Fromm (The Art of Loving) writes: Infantile love follows the principle: I love because I am loved! Mature love follows the principle: I am loved because I love! Immature love says: I love you because I need you!Mature love says: I need you because I love you! Fromm also writes: Paradoxically, the ability to be alone is the condition for the ability to love. This is the case since if one has the ability to be alone, one will not seek love in order to fill a void due to early deprivations, but will seek it in order to live a more fulfilled and a more pleasurable life.  When we look closely at our life we may notice that many events seem to repeat, many relationships seem to resemble the last one. It seems like aspects of life repeats akin to a broken record. Why? Do we really have choices in our behavior, or do we seemingly behave in preprogrammed ways? To answer these questions we need to review how brain works. Brain is shaped by experience. A new experience results in formation of many neural connections that result in adaptation and response to the experience. Thus our brain is formed (wired) by our experiences starting from our early formative years. Every time a given experience is repeated the corresponding neural networks are strengthened. This statement is a direct corollary of Hebbian axiom which says that the neurons that fire together wire together. Brain can be thought of as an information processing organ (an organ of compare and contrast), in the sense that when faced with a stimulus, it performs very fast correlation-like operations with what it has stored in memory to find the closest match to the stimulus just encountered. The correlations are performed with stored events that are more emotionally significant. Emotional significance is marked by Amygdala – an almond-shape set of neurons located deep in the brain's medial temporal lobe (one in each hemisphere), very close to Hippocampus which manages organizing, storing and retrieving memories. In humans and other mammals, this subcortical brain structure is linked to both fear responses and pleasure. Amygdalae therefore assign emotional significance and information to stimuli. Once the closest match is determined the emotional response will essentially be the same as the response corresponding to the past experience (existing wiring in the brain) with some modifications. This is how we repeat our past. Freud called this phenomenon “Repetition Compulsion”, or the compulsion to repeat past trauma. An implication of the above assertions is that we unconsciously seek to repeat what is known to the brain. Thus we unconsciously seek similar relationships to the ones we have experienced before. And what is even more astonishing is that even if the relationship is inherently different, our behavior will resemble the past relationships (activation of the same neural pathways), thus changing the new relationship, in essence, to be similar the ones we have experienced in the past. After all, that is all that our brain knows! In psychological terms this is known as projective identification. It means that we may project the image of a past relationship onto our current relationship and the partner may identify with the image and act it out – resulting in repetition of the past! This happens since brain will try to compare the current relationship to what it has stored in its neural connections, and respond in the same way. Projection identification then is brain's attempt to adapt to a new experience based on what is learned in the past. How can we then avoid repeating our past? The answer to this question is quite simple! I mentioned above that brain is shaped by experience. Thus if we have a new experience in which we do not respond in the old ways, then new pathways in the brain are formed that conform to this new experience. As this experience repeats newly formed neural connections get stronger until they become the dominant connections in the brain. However, this change usually occurs in therapeutic settings in which the therapist, aware if his own counter transference and internal processes, can present the client to a new relational experience and, resist and not identity with the projected image by the client. Thus it is primarily within the therapeutic relationship that change occurs. This also means that the therapist must have done his/her own work, otherwise there is high likelihood that he/she will either identify with client's projected image (projective identification), and/or project his own past onto client (countertransference). Healing can also occur in our day-to-day relationships as well, if we are aware of our internal processes, and become aware when our partner is projecting an image onto us (reacts to us in a programmed way based on his/her past). When we resist the temptation to identify with the projected image or project our own, and when we can be lovingly present and nonjudgmental, when, we are aware of our self and maintain a strong sense of self, we then pave the way for healing and change. Over time, as this process repeats our parter experiences a different reality from what he/she is used to, which will result in formation of new neural pathways (healing). In conclusion, I need to mention that any conscious attempt to oppose our fate (our predicatable behavior) will fail as I have indicated in a past blog. It simply will result in the strengthening of the same neural pathways that we intend to oppose or change. Change occurs through acceptance. “It is only by making the past alive again for a person that a true growth in the present is facilitated. If the past is cut off, the future does not exist.” ― Alexander Lowen, Bioenergetics  Why are we chronically unhappy? When I speak to practically anyone around me, I hear unhappy voices, see grim faces, and contracted bodies. Most people today complain of being unhappy and not satisfied in life. Of course everyone's ego ideal is to live a happy life and to “live life to the fullest”. But the illusion of a happy life seems to elude most people. What is happiness? We can say that we are generally happy when we feel pleasure in our body. Pleasure is feeling which like all other feelings is felt in the body. It is related to expansiveness and openness. Are we then incapable of feeling pleasure to a large extend? The answer based on what people say regarding being unhappy must be “No”! People seem to be able to sense excitement which results in very short lived sensation of pleasure. Excitement is a sensory phenomenon that diminishes shortly after excitement ends. People seek excitement and thrill in order to feel some level of aliveness in their bodies. We live in a narcissistic age, in which image is more important than reality (it may even replace reality), consequently our true self is denied, and replaced with an image. If we deny our true self, we also must by very definition deny our feelings as feelings are perceptions of emotions that originate in our body – our true self. We also had to cut off our feelings as children when our heart was broken through many disappointments, rejections, and loss of love by our significant caretakers. The narcissistic identification with an image and denial of our true self also serve to compensate for the shame of not being seen for who we were and consequent rejection and heartbreak by our caretakers. Having to deny or cut off our feelings all that is left is excitement which gives us a passing moment of feeling “something” which quickly fades. The more alive we are the more we feel, and conversely the more we feel the more alive we are. Dead people have no feelings. Having suffered many rejections and heartbreaks, we become fearful of life and aliveness. Being alive means feeling our emotions, but this will take us back to when we suffered heartbreaks which are too painful to bear. We thus develop a fear of life and living. We seek refuge in our head and deny our body, and focus on achievements, power, money, thrills and excitements, push ourselves to the limit until life breaks us down (heart attack, cancer, auto-immune diseases, etc). We have thus failed! Ironically it is this failure that may provide us with the possibility of recovery. For some this breakdown occurs too late, making it very hard to recover. For some the breakdown provides a moment of self reflection and change in the direction of life. To paraphrase John Pierrakos, MD (co-founder of Bioenergetic Analysis): One of most important tasks of therapy is to help our clients before life breaks them down. To regain our ability to feel pleasure and the capacity to live a happy life, we need to recover our body. We need to breathe, open and soften the thoracic cage which keeps our heart in isolation in order to protect us from heartbreak. If we don't breathe, we won't feel. Dead people do not breathe and do not feel. Suppression of feelings occurs through chronic contraction of musculature responsible for expression of those same feelings. Thus, we also need to release the tension held in our tight musculature which contains a record or our traumas and heartbreaks. Earlier I pointed out that pleasure is related to expansion and pain/anxiety to contraction of body and musculature. The converse must also be true, in that our capacity to feel pleasure is greatly diminished if our body is tight and contracted. I will end this blog by quoting Alexander Lowen MD (founder of Bioenergetic Analysis): “We deaden our bodies to avoid our aliveness, and then pretend to be alive to avoid our deadness.”  Narcissism The term Narcissism is derived from the Greek mythology of Narcissus. Narcissus was a handsome Greek youth who rejected the desperate advances of the nymph Echo (Greek mythological symbols). As punishment, he was doomed to fall in love with his own reflection in a pool of water. Unable to consummate his love, Narcissus pined away (grieved) and changed into the flower that bears his name, the Narcissus. The term narcissism means love of oneself, and refers to the set of character traits concerned with self-admiration, self-centeredness, self-regard, and grandiosity. The name was chosen by Sigmund Freud. The definition of narcissism that I present in this blog is based on the work of Alexander Lowen M.D. (1985). Lowen (1985) sees both psychological as well as cultural aspects to narcissism. Narcissism, on a psychological level, denotes an exaggerated investment in one’s image at the expense of the self. Narcissists are more concerned about how they appear than what they feel. On a cultural level Lowen sees narcissism as a loss of human values, a lack of concern for the environment, for quality of life, and for one’s fellow human beings. The narcissism of the individual parallels that of the culture, in that we shape our culture according to our image, and the culture in turn shapes us. Lowen further states that in his forty years of practice (prior to publication of his book on narcissism in 1985), he has seen a marked change in the personality problems of people consulting him. The neuroses of earlier times represented by guilts, anxieties, phobias, or obsessions are not commonly seen today. Instead, he states, he sees people who complain of depression, lack of feelings, an inner emptiness, a deep sense of frustration and unfulfillment. This absence of guilt and anxiety coupled with lack of feelings give one a sense of unreality about these people. Their performance – socially, sexually, work seems to be too efficient, too mechanical, and too perfect to be human. They function more like robots than human beings (Lowen, 1985). Postmodernism Postmodernism emerged from critique of modernism. Thus the best way to understand postmodernism is by first explaining modernism. The modern era began in late 17th century, with the appearance of artisans and entrepreneurs in the cities. This period coincided with the beginning of capitalism. Modernism ended sometime in 1960s. Postmodern era essentially started in 1960s, although elements of it can be traced back to earlier in the 20th century. Many argue that the main difference between the two eras has to do with question of unity, wholeness and totality. People in modern era were searching for some kind of totality, a unified way of describing the world, a unified set of values, culture, and life style. According to most postmodern theorists not only have we lost the possibility of totality in our lives, but we no longer care about it. Today totality has disappeared so completely that we don’t even remember that it was ever possible! Most of the ideas that we study in schools were created during the modern era. So we are still taught that we ought to have a feeling of wholeness in our lives, or that we have to have an image of the world in which all the pieces fit together. Most postmodern theorists however, believe that the loss of totality (grand narrative) is a good thing. Quest for wholeness or totality will no longer result in fascism or other dictatorial forms of governance, as wholeness and totality no longer exist. For example the grand narrative (totality) for Hitler was the supremacy of the Germans and the Aryan race and their destiny to rule the world. The notion of postmodernism put forward in this blog is that which is presented by Fredric Jameson (1991). Jameson still finds value in talking about totality. His point of view is that totality is still a good idea, because we should try to understand how all the pieces of our world and our experience fit together. During the modern era production lagged behind consumption. Factories struggled hard to produce what consumers demanded. There was a need for more educated people to streamline production, and make factories more efficient. Modern culture had respect for universities, science, and scientists. There was a relentless search for totality in modern times, a totality that could solve modern problems, and can make sense of the world. Modern art also reflected this search for meaning and totality. However, starting in 1960s, due to tremendous advances in forces of production (more modern factories, better tools, etc), consumption began to lag production. Thanks to advances in the forces of production there was in increase in surplus value, or simply profit. This increase in profit then was partially spent in advertisements to increase consumption to further increase profit. The culture of postmodern capitalism transformed from valuing scientific research and endeavors to a culture of consumption. Madison Avenue turned into a force that shaped our lives while it encouraged consumption. Thus was created a culture around consumption (postmodern culture), which now shapes our lives and behavior to a great extent. This is the essence of Jameson’s perspective. Jameson (1991) contends that modernity believed that it could represent reality in simple literal signs (ways of describing real world objects, in which signifier is the form of the sign and signified is the content of the sign.) and was troubled by the possibility that these signs might not have actually represented any reality beyond themselves. Postmodernity no longer worries about this, as it assumes that signs exist by themselves, detached from any external reality. Today’s most images and objects are “simulacra” or copies of the past originals. Thus we observe cars that look like those of 50’s, but totally unrelated, clothes that look like those of several decades ago, but unrelated. Within each postmodern cultural artifact (buildings, songs, films, etc), signs are thrown together in random ways. They come and go for no apparent reason. The best way to understand these ideas is to turn the TV on, and the cutting edge of postmodernism can be clearly seen in “infotainment”, and “infomercials” in that we are not sure if we are watching news or an entertainment show or a commercial. An important perspective of postmodernism can be observed by studying postmodern art, which is a term used to describe an art movement which was thought to be in contradiction to some aspect of modernism, or to have emerged or developed in its aftermath. The following pictures of shoes of Van Gogh and the shoes of Andy Warhol depict the differences between modern and postmodern art very clearly. The first and most evident in Warhol's shoes is a new kind of flatness or depthlessness, a new kind of superficiality in the most literal sense, perhaps the most important formal feature of all the postmodernisms. One can also observe certain lack of feelings in the Warhol’s shoes, albeit it might be aesthetically pleasing. While Van Gogh’s shoes tells a story. His painting conveys certain feelings. Van Gogh's painting conveys a life style, and history behind the shoes as they are depicted. It notifies us of the possible pain the owner endured, given how worn out the shoes are. Modern people felt “feelings”. Their experiences were connected to their inner states, even if their inner states were confused and problematic. They struggled to connect their experiences to each other. Postmodern people are not concerned or disturbed by such issues. Rather than having “feelings”, they merely register disconnected “intensities”. Everyday life itself has its own psychedelic intensity. The more intense the rush, the more “cool” it is. There is something erotically satisfying about the images that play around us. The intense rushes climax quickly, yet the process seems to be eternal. We crave for more, like addicts. It is my belief that the postmodern man who, for the most part instead of having feelings and emotions has sensations of various intensities and through commodity fetishism increases these sensations. He is the agent of reproduction of this stage of capitalism. Postmodern man is a perfect consumer of ideas and commodities in the vast and ever changing spatial postmodern plane, in which past, present, and future all coexist together (fashion of yesterday becomes that of today, etc). This is how late capitalism reproduces itself (cycle of capital through consumption). Postmodern man rejects history and lives on a flat (spatial) ever changing plane. Postmodern man must become empty internally needing constant excitement to feel some aliveness. This excitement may come through consumption of aesthetically pleasing objects. But the excitement wears out and emptiness sets in again, requiring more excitement, and the process repeats.

Based on the way Lowen (1985) defines narcissism, it is easy to conclude that the postmodern man is the narcissist, devoid of feelings, with a sense of emptiness, and heavily invested in, and identifying with an image. The mode of production of late capitalism has created the postmodern culture which shapes the behavior of the individuals in our culture (narcissism), and in turn the individuals reproduce the culture which reproduces the mode of production. In summary, narcissist is what late capitalism needs in order to reproduce itself, and thus to survive, and in turn narcissist is reproduced by late capitalism through its postmodern culture. We conclude this section by paraphrasing Marx who says: Our lives are shaped, above all, by the mode of production that exists in our society. The mode of production means the various tools available to produce goods and services (human labor, natural resources, technologies, investment capital, etc.) and the way we organize those tools. This includes the way we organize ourselves when we use the tools, the way we relate to each other as producers and consumers of goods and services. The situation however, is getting more dire as we are beginning to enter the post-postmodern era. Postmodernism deconstructed all rules, regulations, ideologies, belief system, "religious morality", etc (Jacques Derrida). The psychological correlate of post-postmodernity is autistic existence. Thus we enter an autistic age (not related to autism spectrum disorder). This is the age of isolation and disconnection. Art and architecture (according to Jameson, and Jean Baudrillard and other postmodern theorists) is at the forefront of the change. While places in Vegas that are simulacra of the past bring people together - Venetian, Paris, Flower garden of Belagio, the Forum shops, the new post-post modern architecture of Chrystal Shops or City Center are designed to pull people apart. One hardly runs into anyone in Chrystal Shopping Center, while there are many people there. In Mandarin Oriental hotel the lobby is on the 20th floor. The new hotel lobbies contain essentially nothing, in contradistinction to the postmodern architectures. The entertainment has instead shifted to the rooms. We should expect many more psychological disorders stemming from this stage of development of capital. Instead of creating simulacra for people to adopt and buy, or for people to congregate around, post-postmodern capitalism allows each individual to select his own unique style which may or may not be a copy of the past (simulacra), thus tailoring the production directly to the individual, resulting in ever more consumption of useless goods. References Derrida, J. (1980). Writing and difference. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press. Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism, or, the cultural logic of late capitalism. North Carolina: Duke University Press. Lowen, A. (1985). Narcissism denial of true self. New York: Simon & Schuster.  CAN HAPPINESS BE PURCHASED? Today we live in a world in which practically anything has a price tag and can be purchased. The question that I am posing in this blog is whether happiness also has a price tag and/or whether it can be purchased for the “right” price. Most of us have heard statements such as: I will be the happiest person if only I had that new car, jewelry, clothes, house, etc; or I will be happy if I am in a relationship. Our postmodern world and instant gratification culture certainly provides opportunities to buy objects of our desires, and certainly online dating can provide the latter as we potentially can pick the person of our choosing tailor-made and nicely packaged (size, shape, color, etc) for us. Are we happy though? Invariably the answer is “Yes”, at least for a short time until the excitement subsides. Today we live in a narcissistic world that is reproduced by ever increasing consumption. We consume objects, ideas, relationships, etc, each promising ever lasting excitement and happiness except that the excitement and ensuing happiness disappears very quickly and one has to look for other objects to consume, helping the cycle of capital to continue. The larger question is what is happiness? We generally say: I am happy. Happiness is a feeling not different from other feelings. Feelings are perceptions of emotions (by somatosensory cortex) which are bodily states. Most of us have noticed that when our body is tense and contracted we are not happy. Alternatively, when our body is relaxed and graceful we are happy. Usually we feel some level of happiness for as long as our body is relaxed and not tense. Happiness is also related to pleasure. When we feel pleasure we usually say that we are happy. And conversely when we are happy we sense pleasure in our body. Life is based on pleasure principle, otherwise it would have ceased to exist long ago. We homo sapiens are not an exception to the rule. Our life is based on the pleasure principle. However, due to our many traumas our bodies tense up and contract and we no longer feel the streaming of pleasure in our body. It then takes much work to restore the ability to feel pleasure to our body. Pleasure may cause us to feel anxious (pleasure anxiety). Just remember when we were little, when we had fun, and played and were joyful, we were told to be quiet and/or be still, etc, or were punished for it. We then tensed up our body to conform to the wishes of grown ups (our significant caretakers), reducing our abilities to feel pleasure. Alternatively, from an energetic point of view, one can also say that when the waves of excitement stemming from the inside of our body hit the tense and contracted musculature, the result is anxiety. Most of us may have experienced that after being happy and joyful for a while, all of a sudden we get a sense that something bad may happen which quickly ends our joy and happiness. In the absence of living a pleasurable life, we tend to seek excitement, the sensation of which creates short lasting streams of pleasure and happiness. But as the excitement fades away, so does the pleasure and happiness. And unfortunately this is the state of our society, that is seeking and registering intensities of stimuli as excitement which subside quickly, only to be replaced by others. We then become perfect consumers of goods who help reproduce our socioeconomic system. In this process our true self is denied, and instead we identify with images, ideas, etc, leading to a narcissistic existence. Happiness is the perception of pleasurable state of the body. Happiness can last long if our body is graceful and soft, when we are content and lovingly accept life. This however, does not mean that pain (due to illness or other unforeseen events) will not exist, but it means that in most cases pain will be short lived, and once the state of grace is restored to the body, pleasure and happiness return. Our body will be soft and graceful when we are self aware and express our feelings appropriately. Repression of feelings results in a contracted and tense body and is more associated with displeasure. In a graceful body state, breathing is pleasurable, and when our body is graceful, movement is pleasurable. When our body is soft and graceful, we can feel the pleasure of loving and being loved. In conclusion, I must state that happiness bought is nothing but narcissistic compensation for a life devoid of pleasure and body devoid of grace. "We deaden our bodies to avoid our aliveness and then we pretend to be alive to avoid our deadness" - Alexander Lowen, MD  LOVE, INTIMACY, AND ATTACHMENT My client came in looking better and not as disheveled as in prior sessions (I have seen him for a couple of months). He started sobbing almost as soon as he arrived in my office for which he apologized! I assured him that crying was part of his healing and that his tears would wash away his deep sadness. Once he calmed down a bit (a good two minute or so), I asked him how he was feelings. He replied, he felt utterly alone, except for when he is in the office with me. He mentioned that sometimes he felt there was no hope for him as his despair was just too great to bear, and he did not know how to handle it. He mentioned that he was questioning if life was worth living! I asked him to look out the window and see the beauty of nature, the mountains with snow on them, the trees, and the blue sky. He replied, they just reminded him of his past very difficult days, except perhaps watching the mountains with snow on them. He said to me that he felt he was living a false life in the past. “He had just been walking out there”, he said. He had lied to himself about his life and how bad he felt it was, he said. He spent time at his girlfriend's house whom he did not love, even though she assured him on many occasions that she loved him. He felt really bad about this as he felt he was using her as he did not have much feelings about her. He mentioned that since he started to work with me, he had become aware of the unreality of his life. He had to numb himself and live in a fantasy world (created in his mind) in order to be able to not feel the reality of his life and his (existential) pains. He then went on to ask how he could have the feeling he had in the office with me “out there”. At this point I had tears in my eyes which he noticed and started to cry softly. I replied to him that this would happen but it would take some time. He needed to experience his connection with me longer before he could feel it “out there”, I told him. I explained the neuroscience of human connections/relationships, in a simplified way, which he understood (I have noticed that when I explain the scientific reasons behind my clients' feelings, it reduces their shame regarding their symptoms). I further told him that he needed to “take” in his connection with me, my care and love for him, unconditional and nonjudgmental acceptance of him, and my empathy for him. In doing so new neural pathways would form in his brain that would correspond to this new experience and would fill the void that was left in his heart due to his early traumatic experiences. My statement put him at ease and he noticeably calmed down. I knew that he did take in the connection with me, as he was attaching to me very strongly. I have become an attachment object to him. I asked him if he could take in the love (to whatever extent) that his girlfriend was offering him. His reply was an immediate “no”. I asked him why was it then that he could take in my care and love for him. His replied you don't expect anything from me. You are just sitting here and don't need anything. I then asked him if the reason for this was that he felt that he needed to respond to her in some way, and needed to do something. His reply was “yes”. I asked him to imagine that he did not have to do anything about his girlfriend's love for him, and that he did not have to meet her expectations. Could he then take in her love for him? After taking some time, he then replied, yes he could. But if there were no expectations of me, he emphatically stressed. My hope for him was that if he could allow himself to take in her love for him, it could also create love in him (for her) over time. Most people with oral deprivations in early infancy suffer from conflicting conditions. On one hand they long for connection and contact, but at the same time when contact is offered they reject it and/or become enraged. This is analogous to a baby who wants the breast and cries profusely, but when the breast is finally offered he bites it. I would like to emphasize the profound statements made by this client. He did not experience unconditional love from his mother for which he longs but cannot receive it when it is offered as his mother's love (if there was any) for him was always conditional. This is the reason why experiencing and eventually accepting of my unconditional love and care (along with optimal frustration which is necessary for growth and eventual separation) for him is so crucial in his healing. This is the re-parenting that is talked about in object relations theory. Here comes my responsibility as a therapist. In my work with him, I have awakened his longing for contact, for love, and for connection. I have to accept that and remain present with him, and “optimally” frustrate him, albeit unintentionally, so that he can “grow”, and eventually internalize his connection/relationship with me. I need to be able to tolerate his infantile attachment to me, and not be scared by it. I also need to process my own feelings and what comes up for me when I am an attachment object to him. My own past traumas will possibly be triggered, albeit to an imperceptibly small degree as I have worked through my traumas over the past years. I also have to be able to tolerate his oral rage toward me when it finally is activated. Also he needs to accept the limitations of my care and love (He cannot take me home with him!). Eventually I will (inadvertently) let him down, which may evoke his anger and rage toward me, similar to the baby who longs for the breast but then bites it when it is offered as the baby cannot tolerate frustration. Wilhelm Reich, MD says: The root cause of all neurotic disturbances are disappointments in love. I believe this to be true, and it is the task of therapy to mend the cuts and heal the wounds. And Robert Hilton, PhD says: We were all wounded in relationships, therefore it takes a relationship to heals us. I will end this post with a quote from Ronald David Laing, MD (The Divided Self): (This quote is about a schizophrenic patient who has recovered) “It was terribly hard for me to stop being a schizophrenic. I knew I didn't want to be a Smith (her family name), because then I was nothing but old Professor Smith's grand daughter. I couldn't be sure that I could feel as though I were your child, and I wasn't sure of myself. The only thing that I was sure of was being a 'catatonic, paranoid and schizophrenic'. I had seen that written on my chart. That at least had a substance and gave me an identity and personality. [What let you to change?] When I was sure that you would let me feel like your child and that you would care for me lovingly. If you could like the real me, then I could too. I could allow myself just to be me and didn't need a title.”  WHAT IS SELF LOVE? Yesterday one of my clients, who is facing many life challenges, asked: “What is self love?” I asked him to explain what an ideal loving mother would do for her infant/child. He replied: “She would nurture her baby, nourish him, hug him and give him contact, she would unconditionally love him, accept him with empathy, would not judge him, she would respect the young human, she would put the child in his bed with kindness when he is tired, she would not hurt/harm him emotionally and physically, she would have empathy for him and his growing pains and thus would know when he is in need of connection and contact and can provide it for him.” I then told him, when one treats oneself just like this ideal mother would treat her young child, one loves himself. Thus we love ourselves when we are aware of our needs and our state of mind/body, can freely express ourselves, have compassion for ourselves, will not do anything that harms our body/mind, take care of ourselves when we need rest, and nourish/nurture ourselves when needed, will not judge ourselves and are kind to ourselves, etc.. Incidentally, I told him that love for another starts from love of the self. If one cannot love oneself, love for the other is merely an infantile attachment or passing infatuation and not mature love. HOW TO LOVE THE SELF? Now that I know what self love is, how can I learn to love myself, my client asked. I told him that he could not learn to love himself anymore than he could learn to feel any other feeling. Feelings occur spontaneously. We thus cannot learn to love someone or ourselves. He asked me how he can develop self love then. I mentioned to him that when an infant/child experiences the unconditional love, nonjudgmental acceptance, empathy, and care of his mother, he develops the sense that he must be good and he must be lovable and worthy of love. He than will love himself because he has experienced love. Viewed differently, if he experienced all these he would internalize his mothers love and would then love himself. But if an infant/child did not experience these, he would search for love in vain for the rest of his life to compensate for what he did not receive, and would consequently suffer man heartbreaks. Or defensively, he might close his heart completely to love. He then told me that this is very depressing. Are you telling me that I can never love myself if I did not receive what I needed from my mother? It is not so bad, I replied. You can still develop self love and become a loving person. How, he asked? I said to him we were all hurt in a relationship, it thus takes a relationship to heal us. I told him that he needed to feel my care and love, nonjudgmental and unconditional acceptance, and my empathic attunement to him, and be able to take them in over time and once his trust was established. He needed to feel that I am impacted and touched by his experience of life. In other words he needed to receive from me what he did not receive from his mother. If he was able to take these in for long enough time he would internalize them and would then be able to love himself and can become a loving person. Or from a neuroscience point of view new neural pathways will form in his brain that would correspond to this new experience, one of being seen for who he was and in a caring and loving way. He asked why couldn't he get these in a romantic relationship? I replied, that romantic love was not unconditional, nor would it be necessarily healing. He would have responsibilities in a romantic relationship. But in his therapeutic relationship with me, he needed to just receive my loving presence and empathy and did not need to do anything. He did not need to care for me anymore than an infant/child did not need to love and care for his mother. The love of the mother was just there for him to enjoy. He asked how I was touched by his experience, to which I replied that when he shared a deep shame evoking experience with me, I had tears in my eyes which he noticed and which resulted in a shift in him. His shame disappeared as he felt seen non-judgmentally by me and felt my empathy. He felt that my heart as well as his were touched, and we resonated (limbic resonance) in that session. But as a therapist I also have responsibilities. Once I show my care, empathy and loving presence to a client, I may open up his longing for contact and connection which I cannot fulfill, nor should I. I need to take responsibility for this and accept the consequences of it, and also accept my helplessness to rescue him as he is an adult and ultimately responsible for himself. This is an important part of healing. Many aspects of what I am discussing here are part of relationally based therapies, but they also include a feminist therapeutic model which posits that therapy is mutually transformative. It is not just the client that transforms, therapist is also transformed in the process. This is based on this new egalitarian model of therapy. I would like to end this with a quote from my therapist/teacher/mentor Dr Robert Hilton (Relational and Somatic Psychotherapy): “We are whole beings, heart, soul, and sexuality. This wholeness and sense of well-being is maintained through the empathic core relatedness of our caregivers, and more importantly, in their desire to repair misattunement. When this repair does not take place, we become divided and split from our original spontaneous selves ... If misattunment divided us, it is empathic attunement that gives us the possibility of recovery. This kind of attention causes us to feel the preciousness of our souls and the true value of our love ... We slowly become free to choose, love and express our separate and true selves.” Carl Jung was born on July 26, 1875, in Kesswil, Switzerland. Jung believed in the “complex” or emotionally charged associations. He collaborated with Sigmund Freud, but disagreed with him about the sexual basis of neuroses. He founded analytic psychology, advancing the idea of introvert and extrovert personalities and the power of the unconscious. He wrote several books before his death in 1961. Jung's growing reputation as a psychologist and his work dealing with the subconscious eventually led him to the ideas of Sigmund Freud and the man himself. Over a five-year period, beginning in 1907, the two men worked closely together. Jung was widely believed to be the one who would continue the work of the elder Freud. Viewpoints and temperament ended their collaboration and later their friendship. In particular, Jung challenged Freud's beliefs around sexuality as the foundation of neurosis. He also disagreed with Freud's methods, including his assertion that the elder psychologist's work was too one-sided. The final break came in 1912 when Jung published, "Psychology and the Unconscious," which took head-on a number of Freud's theories. After a pause during World War I, Jung picked up his work again, and for the next four decades traveled the globe to study different cultures. His later work led him to what he called "individuation," a process he described as being a melding of the conscious and unconscious. Through it the person develops into his her own "true self." In 1932 Jung was awarded Zurich's literature prize. Six years later he was elected honorary fellow of England's Royal Society of Medicine. In 1944 he was named an honorary member of the Swiss Academy of Medical Sciences. R.D. Laing - BBC Radio 4 Extra  A key figure in the 60s, influential psychiatrist R.D. Laing tells Professor Anthony Clare about the major influences on his life. Ronald David Laing (7 October 1927 – 23 August 1989), usually cited as R. D. Laing, was a Scottish psychiatrist who wrote extensively on mental illness – in particular, the experience of psychosis. Laing's views on the causes and treatment of serious mental dysfunction, greatly influenced by existential philosophy, ran counter to the psychiatric orthodoxy of the day by taking the expressed feelings of the individual patient or client as valid descriptions of lived experience rather than simply as symptoms of some separate or underlying disorder. Laing was associated with the anti-psychiatry movement, although he rejected the label. Politically, he was regarded as a thinker of the New Left. Ronald D. Laing's work was centered on understanding and treating schizophrenic patients. He could perhaps best be termed an "existential psychiatrist." Indeed, one of his early books was on Jean-Paul Sartre, and he used concepts from Sartre, Hegel and others in endeavoring to conceptualize the life and world of the schizophrenic. Laing himself grew up in a bizarre family setting. His parents forbid him to go out of the house alone or play with other children until middle childhood, they repeatedly conveyed the message to him that he was "evil," and when he went out with them he was kept on a leash with a harness. His childhood environment was such as to cause him severe confusion about which thoughts and feelings were his own, and which were "mapped onto" him by his environment. As an adult, he was himself schizophrenic for periods of time, spending some time as a patient in psychiatric wards. As such, he gained a perspective on schizophrenia which was unusual and perhaps even unique for a psychiatrist. That is, he truly understood what the schizophrenic's world looked like from the inside, as well as from the outside. He also had gained, from his own experience, a sense of the kind of situations in family, school, etc., that could drive a person crazy. Laing worked at Tavistock clinic in London with J. Bowlby and D.W. Winnicott. The audio quality is not very good, and the authors of this video cleverly use an "Avatar" to help with clarity and understanding. The interview was conducted when Freud was suffering from incurable jaw cancer and was near the end of his life. |

AuthorHomayoun Shahri Archives

May 2016

Categories

All

|

Ravonkavi Privacy Policy

©2018 Ravonkavi

©2018 Ravonkavi

RSS Feed

RSS Feed